Questions without answers

Exploring the impact on our spaces in Natalie Lang's memoir

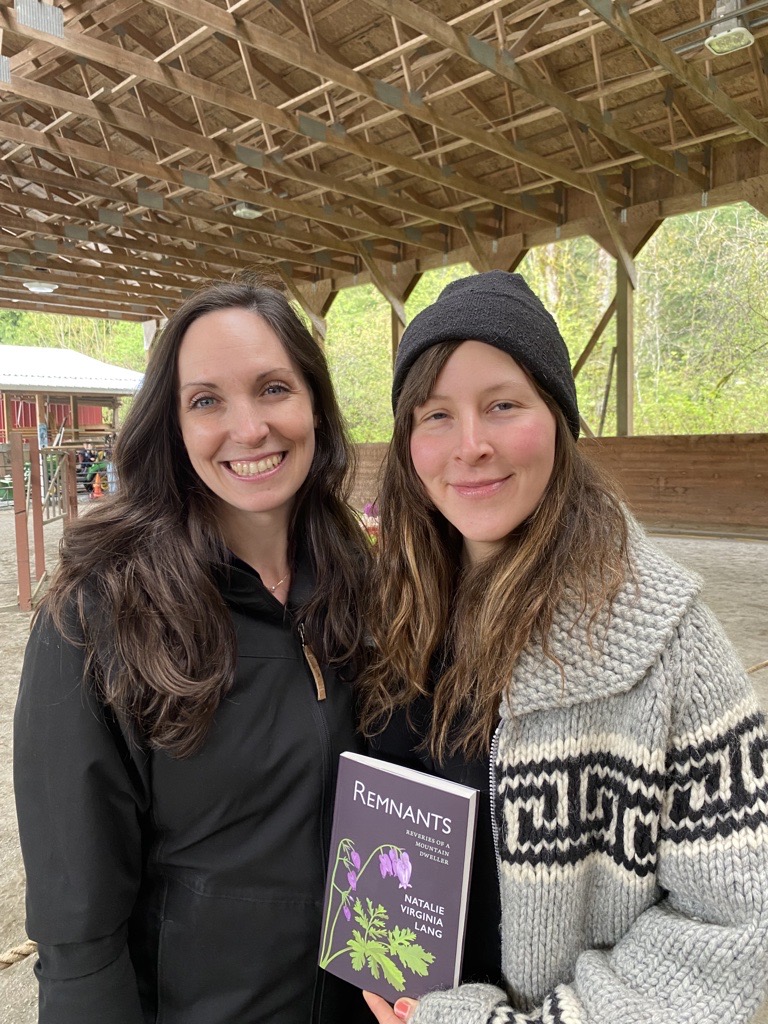

Not every question has an answer. But should that stop the question from being asked? These are the problems Natalie Virginia Lang faced when constructing her debut memoir, Remnants: Reveries of a Mountain Dweller, published by Caitlin Press.

Lang grew up on Sumas Mountain, in Abbotsford. In the 80’s her parents bought a plot of land in the dense backwoods of Straiton, cleared it and erected a home and horse farm. And that small act of settling of a family was only the beginning of the changes Lang would witness first-hand taking place on the mountain. It’s because of these continual transformations to the landscape, with encroaching urbanization, logging, and mining that inspired her to write Remnants to begin with.

“My goal was to offer a space where people could safely ask their own questions and start to build an awareness for their own connection to place,” says Lang.

Upon reading Remnants it’s easy to see this built into the very fabric of the book. Each section focuses on a single season on the mountain, and each season asks the reader to reflect more and more on how they interact with the natural world around them.

However, it becomes quickly apparent that the environmental catastrophes in 2021 – the heat dome in June to the atmospheric river in November – form the crux of this memoir.

For Lang, these disasters acted as an anchor to draw all her thoughts and memories together, to bring the past up to the present.

“When I was starting to write this, the heat dome hadn’t occurred yet. And then it was flooding, and ice, and all these things. And so, the narrative changed and developed as I went through it,” she says. “My initial intention was to write a history of the mountain through my eyes.”

Lang certainly discusses the changes she’s seen over the years on Sumas Mountain, the decrease in endemic life, the changes in the landscape, but the events of 2021 could not be ignored.

“It was almost a forced observation, to say this is what I want to protect,” says Lang. “But I couldn’t include that if I didn’t mention all these things that are happening out there right now. And then mirror them together and show that dichotomy of the history of a place, the beauty of a place, and my connection to a place.”

Lang weaves together these experiences expertly, looking back on the mountain of her childhood, and observing it through the lens of the present. It’s a read that demands personal reflection of the spaces the reader has inhabited, and what they grew up with.

“And I feel like it’s not my job to have the answers. It’s my job to ask questions.”

“The way the world is going, people need to, and I think they want to, start to build connections between their experience in one place and the next. And then the more we build those connections like a spiderweb, the more you start to see how it’s all linked together,” says Lang.

She has done this through her questions. Each one demanding personal reflection, without any real answer.

“And I feel like it’s not my job to have the answers. It’s my job to ask questions,” she says.

She does this by reflecting not only on her personal experiences on the mountain, but also her influence as the descendants of settlers. She acknowledges that she lives on a mountain that was once important to the First Nation’s of the region, even by trying to find the original name of the mountain.

“I had to research outside of regular life to find this information,” says Lang. “And part of it came from just exposure and time in a place and talking to people and asking questions and participating in and what the mountain is.”

Though it’s through this research, that Lang encourages the reader to ask difficult questions about their own spaces. She shares the challenges of global warming, and the disasters she’s witnessed on the mountains in hopes of building that web of connection between the readers’ own experiences.

Ultimately, in the end though, Lang encourages readers to answer the questions she poses themselves.

“You decide,” she says. “You decide what to do about the environment. You decide what the mountain means to you. It’s not up to me to choose for you. All I can do is share what I’ve noticed.”

You can find a copy of Natalie’s book anywhere books are sold, or find her online on her website: natalie-virginia-lang.com